As of 2015, it has been estimated that there are about 120 languages spoken in Utah. Language is deeply connected to the success of Utah’s youth in school. “I did my dissertation on the learning styles of Navajo high school students on and off the reservation. I found that their success goes back to the students becoming confident in speaking their language. When they approach problems or issues, they have that language base where they feel confident, making them feel that they can do the work,” says Dr. Harold (Chuck) Foster.

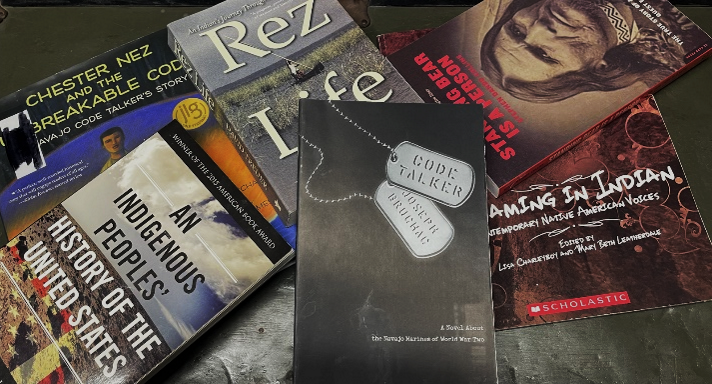

Dr. Foster serves as the American Indian Education Specialist with the Utah State Board of Education, working directly with Indigenous American and Alaskan Native students. Born and raised in Fort Defiance, Arizona, on the Navajo reservation, Foster has been passionate about education since he was young. His passion for language can be traced back to his youth, from his father’s influence. Foster’s father, a Navajo Code Talker, used his native language to send messages for the U.S. military during World War II. This early exposure to the vital role of language helped to shape Dr. Foster’s lifelong passion for preserving language. “All my work has been surrounding American Indian education all my life. For 16 years I was a high school teacher as well as a coach, and I did another 16 years as an administrator, a principal at a middle school and high school,” Foster stated.

With over 32 years of experience in the educational field, Foster has had a front-row seat to observe the benefits of restoring indigenous languages in schools. “When I came here 15 years ago, there was only one language being taught, but we had eight tribes in Utah. Only the Navajo language was being taught,” he noted. Since then, the San Juan School District in southeastern Utah has begun offering some language instruction in Navajo, or Diné. The Tooele School District started offering Goshute classes in its elementary schools in 2023, the result of one of Dr. Foster’s efforts. However, unlike the foreign languages currently taught in Utah’s schools, including Spanish, French, German, and Chinese, the state Legislature doesn’t fund Indigenous language instruction. Dr. Foster has unsuccessfully advocated for this inclusion, unable to find lawmakers willing to address the issue.

Uintah River High School, opened in 1998 and run by the Ute Nation, offers classes on weaving, beading, and speaking Ute. Located in Fort Duchesne, Utah, this school provides a contrast to the two public school districts, Uintah and Duchesne, that serve around 800 Ute children living in the Uintah Basin in eastern Utah. Neither district provides substantial education on the customs or language of the Ute Nation, the largest nation in the region. The Uintah School District has no Ute language classes, and while the Duchesne County School District offers an optional language program in its elementary schools, students must skip recess to participate.

Uintah River High placed in the top 30% of all schools in Utah for overall test scores among Ute students. Meanwhile, test scores for Ute students in the Uintah School District in English alone fell from 10% proficiency to 8% in 2023. It has been proven by studies dating back to the 1920s that students learn best and succeed more when their language and culture are present in their education. A study performed by Nathan M. Castillo and others from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign determined that “students who receive instruction in a language that is not their mother tongue experience a decrease in grades and a higher number of failed attempts. The loss in grade points can be as high as 9.5%.” Uintah River High is working to help its students succeed by following the guidelines proposed by these studies, providing an example for the rest of the state, and, in turn, the rest of the nation.

Dr. Foster reminds us that while “Language and culture don’t make you any smarter, they give you a foundation to build on. It gives a student an advantage; if they speak two languages it gives them a lot more confidence in who they are, where they came from, and where they’re going. That language is very close to an identity.”