Can you walk me through your story?

I’ll start with when I got into flutes. I spent a lot of years in school that had nothing to do with flutes, and I had a congenital heart defect. At a certain point was 1998 the doctors gave me two choices, I could have surgery or I could die. I thought about that for a while. I decided I would have the surgery. For some reason never explained to me, I was on the table for 30 hours. Somewhere along the way, probably something to do with anesthesia, my memory got altered just slightly. It happened to affect the kind of memory you need if you’re going to do family therapy. I decided it would not be ethical to keep doing family therapy, so I quit, and I was looking around for something that would be therapeutic but not require another 20 years in school.

One day, I just happened to hear Carlos Nakai playing the Canyon Trilogy album. You could have stuck my finger in a wall socket or something. It was just electricity. Just ran through me, and I knew immediately that’s what I wanted to do.

Well, I’d already failed at guitars. I bought a Martin guitar, and it hurt my fingers, so I gave it away. When I was about 13, my mother and some of the other mothers decided that we should learn the accordion. And somehow she got my father to put up the money for under 80 beige La Tosca accordion. Well, I can tell you all of the recipients of the accordions hated the accordion, and after my first recital, it magically disappeared, and nothing was ever said about it again. So I had two failures playing musical instruments, and at some point, I decided I would look into woodworking.

I read some stuff on some of the German cabinet makers who did everything by hand. I bought an elaborate workbench and some really nice hand tools, and I never succeeded at one project. I gave those things away. With this illustrious background, I was headed towards flutes, and the odds were there I wouldn’t be able to play them, and that I wouldn’t be able to make them. So, I bought one, and it sounded just terrible. And I bought another one, and it sounded even worse. In those days, there weren’t a whole lot of flutes. In fact, the flutes were on the verge of extinction, until Carlos Nakai came along and showed everyone what they could do.

We were headed on vacation to a place in Arizona, near New Mexico, that was known to be a center of Native American stuff. I thought, well, there’s karma for you. My flute is there. So we drove down and I spent a whole day looking at booths and stores. Didn’t see one flute.

In the very last place I went, I went to the owner. I said, “I just don’t understand this. I came down here to buy a flute, and I haven’t seen one flute.” She said, “Oh, that’s not a problem. My son-in-law makes the best flutes. I’m not going to tell you his name, because he’s a famous player,” and she said, “he’s on tour right now,” which tells you how famous he is, “but his wife can show you the flutes.” It was Saturday, and we were going back the next day, so she called her daughter-in-law and arranged for us to go see the flutes.

I said, “Well, where are they? How do we get there?” And she started this long series of instructions: well, you go south until you see a lightning-struck tree, and you turn left, and after a while, you’ll see a herd of cows, and they’re mainly black and white. You turn right, and on and on and on. After about 12 of these, I thought, “Well, I’m really not going to need a flute. I’m going to die in the desert.” They were the best instructions I ever had. We went right to this little house trailer, and it was way, way, out. There was nothing around but sagebrush, not another trailer, not a teepee, nothing.

We knocked on the door, and this beautiful Navajo woman let us in and showed us some flutes. I didn’t know a lot about flutes then, but I knew something. I looked at the first group and I thought, “Well, I know the name of this game. You know, you dump the worst flutes on the white people, and that’ll be a good step towards revenge.” And she brought out six flutes, and I said, “Well, they aren’t exactly what I wanted.” We went through this several times. After a while, there were over 20 flutes out there, and she had brought out the best ones first.

So I left with no flute. Driving back to Salt Lake, I at some point decided, well, I’m just going to have to do it myself. There wasn’t a whole lot of help back then, because there were very few flute makers, and most of them, frankly, didn’t know anything either.

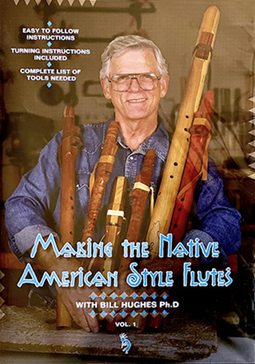

There was a little series of paperback monographs by Luke Price, but they were all based on higher math. Well, I did worse at higher math than I did at woodworking and guitar playing, so they didn’t help me at all. I just started doing what I knew was right. I changed at least one thing on each flute to see if it was better or worse, and after throwing away about 100 flutes, I made a few keepers. I just kept on that way. After a couple of years, I was making flutes I thought were pretty good, and that’s how I got into flutes.

What was the most fulfilling part of that process?

When the first flute started sounding like something beautiful. You know, it’s not fulfilling to blow on a flute and it makes you want to wet yourself. But when they started sounding musical, that was an invaluable feeling.

I’ve read that you do a lot of work with veterans. How did the veterans become part of that story?

That’s a good question. I’m not sure if I know that. I’ve always had a feeling for vets, and when I got around them and they got their hands on a flute that could play, you could see their faces change.

I’ve always emphasized that my special niche is teaching people at the beginner level how to make flutes. It saves them two to three years of doing what I had to do, and in one long session, say, once or twice a week for three months, they could make a flute. In the classes with their first flute, they don’t know really what’s coming next. I’m pretty good at having a deadpan face when I want to, so one day, I knew that the flute was going to play, but they did not know that. I just hand them their flute and say, “Blow on that.” And it makes a sound, and their face is transformed.

I understand you made the flute that Nino Reyos played in the 2002 Winter Olympics. Can you talk about that experience?

Nino is significant in his tribe. I think he’s the only one with a master’s degree, so everyone looks to him.

He was the Ute representative in the Olympics, and he was the one who noticed that a lot of the people from the other tribes didn’t have flutes. He said, “I know someone who can make some,” so I did. I made six and gave them to the Olympic Committee to pass out. That shows you what kind of shape things were in then. I mean, that’s 2002, and a lot of the Native flute players didn’t own flutes. That was a problem.

How did that realization affect your approach to teaching?

I have students in Bulgaria, and years ago, I was giving away one flute a month online. It was based on your need for a flute.

I would put on there all the information about the flute that I was going to give away, and you had to give me an email that said why you needed it. And there were some really sad stories. One month, I got this request, and it didn’t even qualify as broken English. It was something like “I request flute, not for self, but for Bulgarian Native American flute society. We only have two flutes.” Later, it came out that what they meant to say was that they only had two flutes they could loan out to people coming to their group, but it sounded desperate to me, so I sent them six flutes.

There’s a guy who goes by Kanu. Kanu is their spiritual leader, and he plays the Native flute. How that came to be, I do not know, but because he plays it, everyone in his group wants to play the Native flute. I’ve sent quite a few flutes there and organized this big meeting online with all of Kanu’s followers. It lasted at least an hour and a half, and they had set it up and arranged for people to come from far and wide and stay with other people. It was a big deal, and I explained to them that if they were going to make any real progress, they needed a flute maker in Bulgaria. I mean, shipping flutes was expensive. I just shipped two flutes there, and it was $300.

Well, these are very poor people. They have no machines for woodworking. They live in the most minimal circumstances. How do you go about having flute makers in the residence there? I told them that if they would find three people who would commit to sticking it out, I would send them the hand tools. After a while, they had a lot of discussions after the online stuff, and they finally found three people who could commit. So I sent them about $4,000 worth of hand tools and my DVDs, and I made myself available to them online. Their clock is very different from ours, so I spent a lot of hours at two and three in the morning with their budding flute makers. It’s paid off in having two flute makers in Bulgaria; one of them had to drop out.

What role do you think art and the making of your flutes play in fostering communication within people?

The flutes foster communication, but I don’t mean that in the sense that they foster communication between the person with the flute in his mouth and me. I mean it in the sense that it fosters communication between themselves and spirit.

I don’t know any other way to say it. I don’t like the word God, so I don’t use it, but whatever’s beyond whatever’s higher to them, it helps him get in touch with that. We talk about the Native Americans’ love for four directions, but I believe there are seven: north, south, east, west, up, down, and within. It’s the within that helps you get in touch with things.

Native Americans view music differently than we do. For us, you get your guitar, then you go buy some music, and then you hire someone to teach you the music that someone else wrote. Well, they frown on that. They think that the music is in you and that the purpose of the flute is to let it out. In essence, you’re reading yourself and letting that come out through the flute. And if you can do that, then you’re being musical.

What did making flutes help you discover about yourself?

I don’t always have to fail at woodworking, and I’ve learned to try different things. I mean, when I first started, I had to learn everything. You have to be willing to take some wild guesses at something and it might not work. You have to accept that.

What’s next?

I’ll keep doing what I’ve been doing. I lost my wife in June, so I’ll probably do it twice as much.

Is there a message that you want to communicate through your flute-making to other flute makers or other artists in the community?

My message to some of the hotshot flute makers is to get some control over your prices. Some guys will spend an extra day or so making them look fancy, and all of a sudden you’ve got a $2,000 flute, there’s no better than it was before you put lip gloss on it. I don’t like that, and I don’t like it when flute makers say it’s proprietary, which means I’m not going to tell you. I think they almost lost the flutes because of that. If you know something, speak up and share it with the other flute makers.

Do you have anything else that you would like to share?

I want to emphasize that in the aspect of learning the music and yourself, these are the ideal instruments. They’re tuned to a minor pentatonic scale, and you can learn that scale in five minutes. If you play any combination of those notes, it’s going to sound good. In essence, they are the quintessential improvisational instrument. You don’t have to look at notes, you have to look at yourself. And that’s the big deal in the process of making flutes.